Для цитирования:

Валеро С., Петрович И., Занони Д. К., МакГилл М. Р., Гэнли И., Пател С. Г., Джатин П. Ш. Сегментарная мандибулэктомия у пациентов с плоскоклеточным раком полости рта: онкологические исходы и критерии отбора для реконструкции свободным малоберцовым лоскутом. Голова и шея. Российский журнал. 2019;7(4):8–17.

For citation:

Valero C., Petrovic I., Zanoni D.K., McGill M.R., Ganly I., Patel S.G., Shah Jatin P Segmental mandibulectomy in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma: Oncological outcomes and selection criteria for fibula free flap reconstruction. Golova i sheya. Rossijskij zhurnal Head and neck Russian Journal. 2019;7(4):8–17 (in Russian).

Цель исследования: Пациенты с распространенным плоскоклеточным раком полости рта (ПРПР) имеют неблагоприятный прогноз заболевания, несмотря на применение агрессивной мультимодальной терапии. Некоторым больным для достижения онкологически полной резекции требуется сегментарная мандибулэктомия. Пациенты, подвергающиеся сегментарной мандибулэктомии, особенно удалению передней дуги и тела нижней челюсти, имеют значительные функциональные и эстетические проблемы; таким образом, реконструкция резецированного сегмента нижней челюсти становится неотъемлемой частью плана операции. До операции необходимо провести тщательное обследование, чтобы установить, какой тип реконструкции является оптимальным и выполнимым в конкретном случае. Целью данного исследования является описание клинико-патологических характеристик и онкологических исходов пациентов с ПРПР, перенесших сегментарную мандибулэктомию в нашем учреждении, а также определение собственных критериев отбора больных для реконструкции свободным малоберцовым лоскутом (СМЛ).

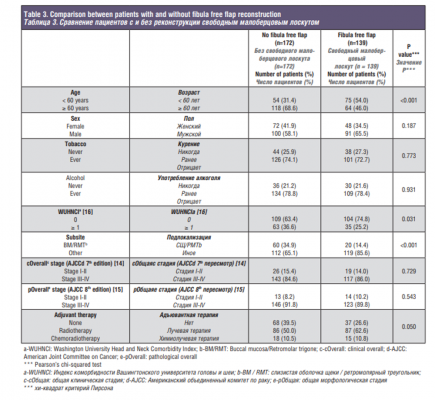

Методы. После получения разрешения от Совета Института был выполнен ретроспективный анализ историй болезни 2082 больных морфологически подтвержденным инвазивным ПРПР, получавших первичное хирургическое лечение в период между 1985 и 2015 г.г. в нашем учреждении. В данное исследование были включены пациенты, которым проводилась сегментарная мандибулэктомия (всего 311 пациентов). Чтобы протестировать собственные критерии отбора для реконструкции свободным малоберцовым лоскутом, мы сгруппировали пациентов согласно типу реконструкции: пациенты с реконструкцией СМЛ (n=139, 44,7%) и пациенты без реконструкции СМЛ (n=172, 55,3%). К интересующим нас конечным точкам относились общая выживаемость (ОВ), опухоль-специфическая выживаемость (СВ) и вероятность отсутствия локального, регионарного или отдаленного рецидива (ВОЛР, ВОРР, ВООР). Для сравнения переменных между группами мы использовали хи-квадрат критерий Пирсона. Кривые выживаемости рассчитывали по методу Каплана–Мейера, а различия в выживаемости сравнивали с использованием логарифмического критерия. Нескорректированные отношения рисков (ОР) были рассчитаны с использованием модели пропорциональных рисков Кокса.

Результаты: Средний возраст больных составил 64 года (от 28 до 100 лет), при этом 61,4% больных были мужского пола. Почти у 90% пациентов были диагностированы опухоли III–IV стадий. Наиболее распространенной локализацией первичной опухоли была нижняя альвеола (52,1%). Инвазия в кость наблюдалась у 69,8% пациентов, и у 6,1% края резекции кости были положительны; эти пациенты имели неблагоприятный прогноз, и лечение их было проблематичным. Для всей когорты (n=311) среднее время наблюдения составило 32 месяца (диапазон 11–87). Пятилетние ОВ и СВ составили 45,2% и 63,9% соответственно. Пятилетние ВОЛР, ВОРР и ВООР составили 71,3%, 83,5 и 83,3% соответственно. Пациенты с реконструкцией СМЛ были моложе (р<0,001) и имели меньше сопутствующих заболеваний (р=0,031). Среди пациентов с СМЛ также был более низкий процент опухолей слизистой оболочки щеки или ретромолярного треугольника по сравнению с пациентами без СМЛ (14,4% против 34,9%; pр<0,001). Этот факт явно демонстрирует ошибки отбора среди пациентов, которым проводилась реконструкция СМЛ. 5-летняя СВ в группе пациентов с СМЛ составила 69,6% по сравнению с 58,0% в группе без СМЛ (ОР=0,634, 95% ДИ 0,409–0,984; p=0,042). Не было найдено существенных различий при анализе ВОЛР между группами; 5-летняя ВОЛР в группе пациентов с СМЛ составила 74,2%, а в группе без СМЛ -68,6% (ОР=0,742, 95% ДИ 0,462–1,189; p=0,215). Вывод: сегментарная мандибулэктомия с реконструкцией СМЛ остается методом выбора в правильно отобранной когорте больных ПРПР. В нашей группе из 2082 пациентов с ПРПР 15% нуждались в сегментарной мандибулэктомии, и почти у половины из них была выполнена реконструкция СМЛ. В целом, более молодые пациенты с меньшим числом сопутствующих заболеваний и с вовлечением в процесс переднего свода или тела нижней челюсти являются лучшими кандидатами для реконструкции СМЛ. Это подчеркивает необходимость тщательной предоперационной оценки и наличия строгих критериев отбора. Пациенты с положительным краем резекции кости имеют неблагоприятный прогноз, и лечение таких больных является сложной задачей. Необходимо разрабатывать новые методы интраоперационной оценки края резекции кости.

Ключевые слова: ротовая полость; плоскоклеточный рак; сегментарная мандибулэктомия; свободный малоберцовый лоскут; реконструкция

Финансирование: это исследование финансировалось Fundaciо`n Alfonso Martín Escudero и грантом Национального Института Здравоохранения/Национального Института Рака (NIH/NCI) США P30 CA008748. Конфликт интересов. Авторы заявляют об отсутствии конфликта интересов.

Для цитирования: Валеро С., Петрович И., Занони Д. К., МакГилл М. Р., Гэнли И., Пател С. Г., Джатин П. Ш. Сегментарная мандибулэктомия у пациентов с плоскоклеточным раком полости рта: онкологические исходы и критерии отбора для реконструкции свободным малоберцовым лоскутом. Голова и шея. Российский журнал. 2019;7(4):8–17.

Purpose: Patients with advanced stage oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) have a poor prognosis despite aggressive multimodal therapy. Segmental mandibulectomy is required in some of these patients to achieve an oncologically complete resection. Patients undergoing segmental mandibulectomy, particularly of the anterior arch and the body of the mandible, will have significant functional and aesthetic morbidity, and therefore, reconstruction of the resected segment of the mandible becomes an integral part of the surgical plan. Patients must be thoroughly assessed preoperatively to decide which type of reconstruction is optimal and feasible in each case. The aim of this study is to describe the clinicopathological characteristics and oncological outcomes of patients with OSCC who underwent segmental mandibulectomy at our institution, and to define our selection criteria for fibula free flap (FFF) reconstruction.

Methods: After receiving approval from our Institutional Review Board, a retrospective analysis was performed on 2082 consecutive patients who had a biopsy-proven invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity treated with primary surgery between 1985 and 2015 at our institution. For this study, we selected the patients that required segmental mandibulectomy to form our final cohort of 311 patients. To analyze our selection criteria for FFF reconstruction, patients were grouped according to the type of reconstruction: patients with FFF reconstruction (n=139, 44.7%) vs patients without FFF reconstruction (n=172, 55.3%). The outcomes of interest were overall survival (OS), disease-specific survival (DSS) and local, regional, and distant recurrencefree probability (LRFP, RRFP, DRFP). To compare variables between groups we used Pearson’s chi-squared test. Survival curves were calculated according to the Kaplan–Meier method and differences in survival were compared using the log-rank test. Unadjusted hazard ratios (HR) were calculated using the Cox proportional hazard model.

Results: The mean age was 64 years (range, 28-100), and 61.4% were men. Nearly 90% of patients had stage III–IV tumors. The most common primary tumor site was lower alveolus (52.1%). Bone invasion was present in 69.8% of patients and 6.1% had positive bone margins; these patients had poor prognosis and management was challenging. For the whole cohort (n = 311), median follow-up time was 32 months (range, 11-87). Five-year OS and DSS were 45.2% and 63.9%, respectively. Five-year LRFP, RRFP, and DRFP were 71.3%, 83.5%, and 83.3%, respectively. Patients with FFF reconstruction were younger (p<0.001) and had less comorbidities (p=0.031). Patients with FFF also had a lower percentage of tumors in the buccal mucosa or retromolar trigone compared to patients without FFF (14.4% vs 34.9%, p<0.001). There were no differences in terms of sex (p=0.187) or tobacco and alcohol use (p=0.773 and p=0.931). No differences in clinical or pathological staging between groups were observed (p=0.729 and p=0.543, respectively). When evaluating adjuvant treatment, the group without FFF reconstruction had a higher percentage of patients, with comorbid conditions, who could not receive adjuvant treatment compared to the group of patients with FFF reconstruction (39.5% vs 26.6%, p=0.050). Patients with FFF had a 5-year OS of 59.0%, compared to 34.8% in patients without FFF (HR: 0.473; 95% CI: 0.358-0.623, p<0.001). This clearly shows the selection bias for patients who had FFF reconstruction. The 5-year DSS in the group of patients with FFF was 69.6%, compared to 58.0% in the group without FFF (HR: 0.634; 95% CI: 0.409-0.984, p=0.042). No significant differences were seen when LRFP was analyzed between groups; the 5-year LRFP in the group of patients with FFF was 74.2%, and 68.6% in the group without FFF (HR: 0.742; 95% CI: 0.462-1.189, p=0.215).

Conclusion: Segmental mandibulectomy with FFF reconstruction remains the treatment of choice in properly selected patients with OSCC. In our cohort of 2082 OSCC patients, 15% needed a segmental mandibulectomy and almost half of them had FFF reconstruction. In general, younger patients with less comorbidities and with anterior arch or body of the mandible involvement are the best candidates for FFF reconstruction. This underscores the need for a thorough preoperative assessment and stringent selection criteria. Patients with positive bone margins have a poor prognosis and management is challenging. New techniques that better assess bone margins intraoperatively need to be studied.

Keywords: Oral cavity; Squamous cell carcinoma; Segmental mandibulectomy; Fibula free flap; Reconstruction

Funding: This study was funded by Fundaciо`n Alfonso Martín Escudero and the National Institutes of Health/ National Cancer Institute (NIH/NCI) Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748. Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

For citation: Valero C., Petrovic I., Zanoni D.K., McGill M.R., Ganly I., Patel S.G., Shah Jatin P Segmental mandibulectomy in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma: Oncological outcomes and selection criteria for fibula free flap reconstruction. Golova i sheya. Rossijskij zhurnal Head and neck Russian Journal. 2019;7(4):8–17 (in Russian).

Introduction Recent reports in the literature show an improvement in survival in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) over previous decades [1, 2]. In most instances this is attributed to an increase in the number of patients presenting with early stage disease. However, patients who present with advanced stage OSCC still have a poor prognosis despite aggressive multimodal therapy. Some studies have proposed that concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CRT) can be offered as a treatment option, rather than surgery, for advanced OSCC. Nonetheless, response rates for oral cancer are not as good as seen in the larynx and oropharynx, and thus, surgical resection remains the preferred treatment and standard of care for nearly all patients with OSCC [3–6].

Excision of a segment of the mandible is required in some patients to achieve an oncologically complete resection. The indications for segmental mandibulectomy are: (1) Gross invasion of the mandible, (2) Tumor fixation to most of the lingual cortex of the mandible, especially in the edentulous mandible, where a marginal mandibulectomy is not feasible due to loss of vertical height of the mandible, (3) Tumor fixed to the mandible following prior radiotherapy (RT) to the mandible, (4) Massive soft tissue disease surrounding the mandible, (5) Primary malignant tumors of the mandible, (6) Metastatic tumor to the mandible, and (7) Invasion of the inferior alveolar nerve by perineural spread from mucosal or skin cancers [7, 8]. Patients undergoing segmental mandibulectomy, particularly of the anterior arch and the body of the mandible, will have significant functional and aesthetic morbidity, and therefore, reconstruction of the resected segment of the mandible becomes an integral part of the surgical plan [9]. In the past three decades, fibula free flap (FFF) has emerged as the preferred option for the best functional and aesthetic outcomes for mandible reconstruction [7,10]. This procedure is complex and requires significant expertise, planning, and rehabilitative measures to achieve the best outcome. Furthermore, the sequela and complications of the procedure are not negligible. Patients who develop complications clearly have increased morbidity, prolonged hospitalization and increased cost of care [11,12].

Moreover, it has been reported that patients with postoperative complications also have worse prognosis [13]. This is often attributed to advanced stage disease requiring bigger resections, in patients with poor nutrition and comorbid conditions. When segmental mandibulectomy is indicated, patients must be thoroughly assessed preoperatively to decide if FFF is the optimal choice for reconstruction and if the patient is a satisfactory candidate to tolerate the procedure. Thus, patient selection is crucial to achieve the best oncologic and functional outcomes.

The aim of this study is to describe the clinicopathological characteristics and oncological outcomes of patients with OSCC who underwent a segmental mandibulectomy at our institution. Additionally, we studied the differences between patients who had FFF reconstruction and those who had either primary closure without any reconstruction or other type of reconstruction in order to define our selection criteria for FFF.

Material and methods After receiving approval from our Institutional Review Board, a retrospective analysis was performed on 2082 consecutive patients who had a biopsy-proven invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity treated with primary surgery between 1985 and 2015 at our institution. The exclusion criteria were prior history of nonendocrine head and neck cancer, synchronous other mucosal head and neck squamous cell carcinomas, previously treated patients with oral carcinoma and distant metastasis at presentation. From this database, we identified 311 patients (15%) who underwent a segmental mandibulectomy, forming the study cohort. We used the AJCC 7th edition of the TNM staging system for preoperative clinical staging since depth of invasion was not routinely recorded preoperatively for many patients during the early years of this study period [14]. However, all the pathological material was rereviewed and therefore for pathological staging, we used the AJCC 8th edition criteria [15]. The outcomes of interest were overall survival (OS), diseasespecific survival (DSS) and local, regional, and distant recurrencefree probability (LRFP, RRFP, DRFP). OS was calculated from the date of surgery to the date of death or the last date the patient was known to be alive. DSS was calculated from the date of surgery to the date of death or the last assessment of the disease by a member of our multidisciplinary disease management team (DMT). We considered a death an event for DSS if the patient had active disease at the time of last disease assessment. Finally, LRFP, RRFP and DRFP were calculated from the date of surgery to the date of the specific recurrence or last disease assessment. The follow-up interval was considered between the date of primary surgery to the date of last known follow-up with a member of the DMT. Moreover, we analyzed the type of reconstruction after segmental mandibulectomy. During the study period (1985-2015), 454 patients underwent FFF reconstruction after mandible resection for various indications (Osteoradionecrosis, benign and malignant tumors of different histology, reconstruction for primary surgery, for salvage surgery or for second primaries). In this study, we only included FFF reconstruction performed for primary surgery of an index oral cavity SCC, previously un-treated, without metastasis at presentation and without history of synchronous head and neck tumors.

In our study cohort of 311 patients who underwent segmental mandibulectomy, patients were stratified according to type of reconstruction into two different groups: reconstruction with FFF (n=139, 44.7%) and those with other types of reconstruction (n=172, 55.3%). The latter included patients undergoing primary closure, local or regional pedicled myocutaneous flaps and free flaps with or without bone other than fibula.

To compare variables between groups we used Pearson’s chi-squared test. Survival curves were calculated according to the Kaplan–Meier method and differences in survival were compared using the log-rank test. Unadjusted hazard ratios (HR) were calculated using the Cox proportional hazard model. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistica analyses were conducted using SPSS (v25.0, IBM Corporation; Somers, NY).

Results

Patient characteristics and oncological outcomes:

A total of 311 patients with OSCC (15%) underwent segmental mandibulectomy during the study period. Clinical characteristics of these patients are shown in Table 1. The mean age was 64 years (range, 28-100), and 61.4% were men. History of tobacco and alcohol consumption was reported by 73.0% and 78.1% patients respectively. Comorbidities were recorded according to the Washington University Head and Neck Comorbidity Index (WUHNCI), with 31.5% of the patients having a WUHNCI equal or greater than 1 at the time of OSCC diagnosis [16]. The most common primary tumor subsite was lower alveolus (52.1%). The majority of patients (83.6%) had advanced clinical stage tumors (stage III-IV), according to the 7th Edition of AJCC TNM classification [14]. Seventy-six percent of patients had their primary tumor staged as T3-4. Clinically palpable regional lymph nodes were present in 56.6% of patients at diagnosis. Treatment of the neck consisted of, selective neck dissection in 46.9% of patients, comprehensive neck dissection sparing the accessory nerve in 42.1% of patients, and radical neck dissection in 10.6% of patients.

Histopathologic characteristics are listed in Table 2. Depth of invasion greater than 10mm was present in 56.9% of the cases. Bone invasion was present in 69.8% of the patients, of which 30.4% had cortical invasion, 59.9% had medullary invasion and 9.7% were not specified. Vascular invasion was present in 17.4% of the cases and perineural invasion in 31.8%. Positive pathological nodes were found in 176 patients (56.6%). Extra-nodal extension was reported in 30.9% of the cohort.

Assessment of surgical margins showed that 28.0% of patients had negative, 51.8% had close, and 19.9% had positive margins.

Moreover, soft tissue and bone margins were assessed separately. Soft tissue margins were negative in 49.2% of the cases, close in 28.6% and positive in 22.2%. When analyzing bone margins for the entire cohort (n=311), 93.2% had negative, 0.6% had close and 6.1% had positive bone margins. For patients with positive bone margins (n=19), median age was 66 years (range, 30-90), 57.9% were females, and tumor subsite for the majority of patients was lower alveolus (73.7%). The median surface dimension of the primary tumor was 3.3cm (range, 1.5-7.2) and 89.5% of the patients were clinically staged as T4.

For the entire cohort (n=311), pathologic staging according to the 8th Edition of AJCC TNM classification showed that the majority of patients had tumors with an advanced T stage (12.9% T3 and 65.6% T4) [15]. In terms of nodal disease, 11.3% were staged as N1, 16.4% as N2, and 26.4% as N3. Evaluating overall pathological staging, 86.5% of the patients had advanced stage tumors (stage III-IV). When analyzing adjuvant treatment, 55.6% had postoperative RT and 10.6% had postoperative CRT. There were 23 patients who did not receive adjuvant treatment even though it was indicated, either because they refused treatment (n=5, 21.7%) or because they were medically not fit or died within 3 months after surgery (n=18, 78.3%).

Median follow-up time was 32 months (range, 11-87). Five-year OS and DSS were 45.2% and 63.9%, respectively. Five-year LRFP, RRFP, and DRFP were 71.3%, 83.5%, and 83.3%, respectively.

Patient characteristics and oncological outcomes according to type of reconstruction:

We divided our cohort into two groups for analysis: one group included patients with FFF (n=139) and the second group were patients without FFF (n=172) reconstruction. The purpose of this analysis was to define selection criteria for FFF reconstruction. Of the 172 patients who did not have FFF reconstruction, 67 had reconstruction with other free flaps. Ten of these free flaps were with bone other than fibula and 57 had only soft tissue free flaps, the majority of which were rectus abdominis (69.6%). Of the remaining patients, 59 had primary closure and 34 had a regional pedicled flap, with pectoralis major myocutaneous flap being the most common. The 12 remaining patients had either a local flap or a skin graft, and one patient had a custom stainless-steel prosthesis specially manufactured for him based on preoperative imaging.

The comparison of clinicopathologic characteristics between the two groups is listed in Table 3. Patients with FFF reconstruction were younger (p<0.001) and had less comorbidities (p=0.031). Patients with FFF also had a lower percentage of tumors in the buccal mucosa or retromolar trigone compared to patients without FFF (14.4% vs 34.9%, p<0.001). There were no differences in terms of sex (p=0.187) or tobacco and alcohol use (p=0.773 and p=0.931). No differences in clinical or pathological staging between groups were observed (p=0.729 and p=0.543, respectively). When evaluating adjuvant treatment, the group without FFF reconstruction had a higher percentage of patients, with comorbid conditions, who could not receive adjuvant treatment compared to the group of patients with FFF reconstruction (39.5% vs 26.6%, p=0.050). The main difference between the groups in terms of why patients did not receive adjuvant treatment was a higher percentage of patients not being fit to tolerate adjuvant treatment or dying within 3 months after surgery in the group of patients without FFF reconstruction (33.3% vs 23.8%, p=0.443), even though this difference did not reach statistical significance. Survival outcomes by type of reconstruction are shown in Figure 1. Patients with FFF had a 5-year OS of 59.0%, compared to 34.8% in patients without FFF (HR: 0.473; 95% CI: 0.358-0.623, p<0.001). This clearly shows the selection bias for patients who had FFF reconstruction. The 5-year DSS in the group of patients with FFF was 69.6%, compared to 58.0% in the group without FFF (HR: 0.634; 95% CI: 0.409-0.984, p=0.042). No significant differences were seen when LRFP was analyzed between groups; the 5-year LRFP in the group of patients with FFF was 74.2%, and 68.6% in the group without FFF (HR:0.742; 95% CI: 0.462-1.189, p=0.215).

Discussion

Most patients with OSCC requiring segmental mandibulectomy have advanced stage disease and overall poor prognosis. Segmental mandibulectomy is a functionally and esthetically crippling procedure, requiring consideration of reconstruction to restore form and function. Although the best aesthetic and functional results are achieved with FFF reconstruction with immediate placement of dental implants for dental rehabilitation, patient selection for the operative procedure is crucial to minimize postoperative morbidity, mortality and complications. The ultimate goal is to achieve good long-term tumor control and as good a functional and esthetic outcome as can be achieved for the individual patient. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to analyze the survival outcomes in this cohort of patients undergoing segmental mandibulectomy, and to analyze our criteria used for selection of patients for FFF reconstruction.

In our cohort of 311 patients undergoing segmental mandibulectomy, despite aggressive multimodal therapy combining surgery and adjuvant treatment, over half of the patients died during the study period. The 5-year OS and DSS were 45.2% and 63.9% respectively. As expected, a high percentage of our patients (86.5%) had advanced stage tumors with aggressive features, including 56.9% of patients with depth of invasion greater than 10mm, 69.8% of patients with bone invasion, 31.8% with perineural invasion and 30.9% with extra-nodal extension of metastatic cancer.

An important factor that influences outcomes is positive margins, and in this setting of mandible resection, management of positive bone margins is especially challenging and requires some discussion. A thorough preoperative imaging assessment is the first step to minimize the risk of positive bone margins. If possible, bone invasion should be evaluated using both a Computed Tomography and a Magnetic Resonance Imaging scan. Intraoperative assessment of bone marrow scraping from the cut end of the divided bone and studying the smears histologically has been reported to minimize the aforementioned risk by enabling immediate additional resection if necessary [17]. A positive smear would require additional bone resection, although negative smears do not rule out microscopic positive bone margin. New intraoperative techniques are currently being studied to be able to assess bone margins more accurately [18]. Despite employing the technique of bone margin smears, we did have a small percentage of patients (7%) with final positive or close bone margins, similar to what has been reported by other authors [18,19]. We managed 13 of these patients (68.4%) with adjuvant treatment. For the remaining patients, adjuvant treatment was intended, but patients were not able to receive the adjuvant treatment due to postoperative complications. None of these patients were alive at two years following surgery.

When planning reconstruction after segmental mandibulectomy, a carefully thought out selection process is needed to choose the best approach for each individual patient. Even though FFF is considered to be the gold standard functionally and aesthetically, one should consider patient, tumor and physician factors when deciding whether the patient is a suitable candidate for reconstruction with FFF.

In terms of patient factors, the best candidates for FFF are younger patients without comorbidities because this is a complex procedure, with prolonged duration of surgery and length of hospitalization, and the risk of medical and surgical complications is not negligible. The adverse impact of donor-site morbidity is also a consideration, since patients with FFF reconstruction will not be able to ambulate for a longer period of time. The higher percentage of younger patients without comorbidities in our FFF group is a reflection of this selection policy.

Amongst tumor factors, the primary tumor site is the main factor driving the decision for bone reconstruction. Tumors located posteriorly such as in the buccal mucosa or retromolar trigone are often locally advanced necessitating a large soft tissue resection in the masticator space or the infra temporal fossa, as well as bone resection of the ascending ramus of the mandible. Moreover, functional and aesthetic consequences of resecting the posterior aspect and ascending ramus of the mandible are not as significant as resecting the anterior arch or lateral body of the mandible. Therefore, for tumors located posteriorly, FFF may not be necessarily the ideal method of reconstruction. This selection decision is reflected in our cohort where patients with tumors located in the buccal mucosa or retromolar trigone had a lower probability of being reconstructed with FFF. In contrast, for tumors requiring anterior arch or lateral body mandible resections, FFF is the best option.

Lastly, physician factors are an important determinant of the type of reconstruction. Surgeon preferences and expertise in the various types of reconstruction procedures play an essential role in the selection criteria. FFF requires a multidisciplinary team, and it should be performed in tertiary care centers with the necessary expertise, resources and infrastructure for successfully performing the operative procedure and managing the postoperative course and rehabilitation of the patient.

The aforementioned selection criteria for FFF also indirectly influence oncological outcomes. We observed better survival outcomes in the group of patients with FFF reconstruction, but these differences are likely due to selection bias. FFF patients were younger and with less comorbidities, and it is logical that the presence of comorbidities in patients with head and neck cancer has been associated with reduced OS [20]. Moreover, the group of patients with FFF reconstruction had a lower percentage of tumors located in the buccal mucosa and retromolar trigone, which are high risk locations for adverse oncologic outcomes [21–23]. We have previously reported that patients with buccal mucosal cancer had worse prognosis compared to other sites in the oral cavity, mainly driven by a higher percentage of patients with an older age and advanced stage [24]. Similar results were reported by other authors [25].

Another factor which impacts outcome in these patients is the addition of adjuvant radiation or chemoradiation. The group without FFF reconstruction had a higher percentage of patients who could not receive adjuvant treatment, which may have also influenced the worse survival in this group. One of the reasons for this is that a higher percentage of these patients were unfit to tolerate adjuvant treatment, and a higher percentage died before receiving the treatment when compared to the group of patients with FFF reconstruction. Despite this, the rates of LRFP were not significantly different between the two groups.

Our results provide validation of our selection process and management policy used to choose the type of reconstruction after segmental mandibulectomy in OSCC and reinforce the fact that when comparing oncological outcomes for a particular type of treatment, it is important to consider all the differences resulting from selection bias.

Conclusion

Segmental mandibulectomy with FFF reconstruction remains the treatment of choice in properly selected patients with OSCC. In general, younger patients with less comorbidities and with anterior arch or body of the mandible involvement are the best candidates for FFF reconstruction. This underscores the need for a thorough preoperative assessment and stringent selection criteria. Patients with positive bone margins have a poor prognosis and management is challenging. New techniques that better assess bone margins intraoperatively need to be studied.

REFERENCES

1.Amit M., Yen T.C., Liao C.T., et al. Improvement in survival of patients with oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma: An international collaborative study. Cancer. 2013;119(24):4242–8.

2 . Schwam Z.G., Judson B.L. Improved prognosis for patients with oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma: Analysis of the National Cancer Database 1998–2006. Oral Oncol. 2016;52:45–51.

- Elbers J.B.W., Al-Mamgani A., Paping D., et al. Definitive (chemo)radiotherapy is a curative alternative for standard of care in advanced stage squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity. Oral Oncol. 2017;75:163–8.

- Gore S.M., Crombie A.K., Batstone M.D., Clark J.R. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy compared with surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy for oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2015;37(4):518–23.

- Tangthongkum M., Kirtsreesakul V., Supanimitjaroenporn P., Leelasawatsuk P. Treatment outcome of advanced staged oral cavity cancer: concurrent chemoradiotherapy compared with primary surgery. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;274(6):2567–72.

- Gill A., Vasan N., Givi B., Joshi A. AHNS Series: Do you know your guidelines? Evidence-based management of oral cavity cancers. Head Neck. 2018;40(2):406–16.

- Montero P.H., Patel S.G. Cancer of the Oral Cavity. Surg. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2015;24(3):491–508.

- Gou L., Yang W., Qiao X., et al. Marginal or segmental mandibulectomy: treatment modality selection for oral cancer: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018;47(1):1–10.

- Bolzoni A., Cappiello J., Piazza C., Pedruzzi B., Nicolai P. Quality of life in patients treated for cancer of the oral cavity requiring reconstruction: a prospective study. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2008;28(3):120–5.

- Hayden R.E., Mullin D.P., Patel A.K. Reconstruction of the segmental mandibular defect: Current state of the art. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2012;20(4):231–6.

- Kroll S.S., Schusterman M.A., Reece G.P. Costs and complications in mandibular reconstruction. Ann. Plast. Surg. 1992;29(4):341–7.

- Wu C.C., Lin P.Y., Chew K.Y., Kuo Y.R. Free tissue transfers in head and neck reconstruction: complications, outcomes and strategies for management of flap failure: analysis of 2019 flaps in single institute. Microsurgery. 2014; 34(5):339–44.

- Ch’ng S., Choi V., Elliott M., Clark J.R. Relationship between postoperative complications and survival after free flap reconstruction for oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2014;36(1):55–9.

- Edge S.B. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 7th ed. New York: Springer; 2010.

- Amin M.B. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 8th ed. New York: Springer; 2017.

- Piccirillo JF, Lacy PD, Basu A, Spitznagel EL. Development of a new head and neck cancer-specific comorbidity index. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2002;128(10):1172–9.

- Nieberler M., Häusler P., Drecoll E., et al. Evaluation of intraoperative cytological assessment of bone resection margins in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Cytopathol. 2014;122(9):646–56.

- Haase C., Lethaus B., Knüchel-Clarke R., Hölzle F., Cassataro A., Braunschweig T. Development of a Rapid Analysis Method for Bone Resection Margins for Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma by Immunoblotting. Head Neck Pathol. 2018;12(2):210–20.

- Camuzard O., Dassonville O., Ettaiche M., et al. Primary radical ablative surgery and fibula free-flap reconstruction for T4 oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma with mandibular invasion: oncologic and functional results and their predictive factors. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;274(1): 441–9.

- Schimansky S., Lang S., Beynon R., et al. Association between comorbidity and survival in head and neck cancer: Results from Head and Neck 5000. Head Neck. 2019;41(4):1053–62.

- Rizvi Z.H., Alonso J.E., Kuan E.C., St. John M.A. Treatment outcomes of patients with primary squamous cell carcinoma of the retromolar trigone. Laryngoscope. 2018;128(12):2740–4.

- Lin C.-S., Jen Y.-M., Cheng M.-F., et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the buccal mucosa: an aggressive cancer requiring multimodality treatment. Head Neck. 2006;28(2):150–7.

- Lubek J.E., Dyalram D., Perera E.H.K., Liu X., Ord R.A. A retrospective analysis of squamous carcinoma of the buccal mucosa: an aggressive subsite within the oral cavity. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2013;71(6):1126–31.

- Gupta P., Migliacci J.C., Montero P.H., et al. Do we need a different staging system for tongue and gingivobuccal complex squamous cell cancers? Oral Oncol. 2018;78:64–71.

- Camilon P.R., Stokes W.A., Fuller C.W., Nguyen S.A., Lentsch E.J. Does buccal cancer have worse prognosis than other oral cavity cancers? Laryngoscope 2014;124(6):1386–91.

Рецензия на статью

Статья носит оригинальный характер, содержит сведения об исследовании показаний для хирургического лечения рака слизистой оболочки полости рта. Статистической базой исследования является обширный клинический материал более 300 наблюдений. Работа раскрывает важнейшие предикторы принятия решения по выполнению сегментарной резекции нижней челюсти, которые должны быть использованы в дальнейшей реконструкции утраченного фрагмента кости. Надо поблагодарить авторов за серьезное исследование. Рекомендуем к публикации в разделе «Оригинальное».

Review on the article

The article is original in nature, contains information about the study of indications for the surgical treatment of cancer of the oral mucosa, and the statistical base of the study is an extensive clinical material of more than 300 observations. The work reveals the most important predictors of decision-making on the implementation of segmental resection of the lower jaw, which should be used in further reconstruction of the lost bone fragment.

We must thank the authors for such a serious study. The article is recommended for publication in the Original section.